PSPK

PSPK

By: Anindito Aditomo

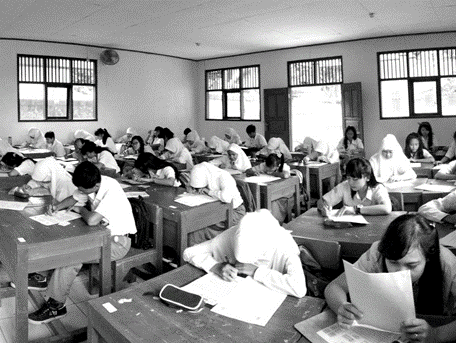

Starting next year, the National Examination (Ujian Nasional/UN) will be replaced by the National Assessment (Asesmen Nasional/AN). This was announced by the Minister of Education and Culture, Nadiem Makarim, a few days ago. According to the Ministry’s plan, the National Assessment will be implemented in all schools and administered to a sample of students in Grades 5, 8, and 11.

The replacement of the National Examination with the National Assessment marks a fundamental shift in Indonesia’s education evaluation system. This change will affect millions of students and teachers across the country. It is therefore understandable that many stakeholders have questions and feel anxious.

Students and parents may wonder about graduation criteria under the new system. Some teachers may be concerned about the limited time available to prepare students for an assessment that is said to be very different from what they are familiar with.

Some school principals may be thinking about how to ensure their schools are perceived as performing well in the assessment. Similar concerns may also be shared by heads of local education offices who wish to demonstrate strong performance to regional leaders.

This article examines the similarities and differences between the National Examination and the National Assessment. My hope is that a better understanding of the National Assessment will help ease the anxiety felt by teachers, students, and parents as they face changes in the education evaluation system.

The first and most important point to understand is that the National Assessment is purely an evaluation of the quality of the education system. It is not an evaluation of individual student achievement. The results of the National Assessment have no consequences whatsoever for the students who participate.

This characteristic distinguishes the National Assessment from the National Examination. The National Examination combined two purposes: evaluating individual students and evaluating the education system.

On the one hand, the National Examination was used to assess each student’s mastery of curriculum content. Its results were also used to determine graduation (until 2015) and as part of the selection process for admission to the next level of education.

On the other hand, the National Examination was used to map education quality and evaluate the performance of schools and local governments. In previous years, the Ministry regularly published National Examination scores for all schools and awarded recognition to “top-performing” schools.

This difference in purpose between the National Assessment and the National Examination has many implications. For example, not all students in Grades 5, 8, and 11 need to participate in the National Assessment. To produce a representative picture of a school, it is sufficient for the assessment to be taken by a randomly selected sample of students.

As a further consequence, National Assessment results are not reported at the individual level. Students who participate will not receive certificates showing their test scores. The results are reported only in the form of school and regional profiles.

This would not be possible under the National Examination. Because it was intended to assess individual achievement, the National Examination had to be taken by all students, and the results were reported in the form of certificates showing each student’s score.

Another implication of the differing purposes of the National Assessment and the National Examination lies in what they measure. As explained above, the National Examination was designed to assess students’ mastery of curriculum content. Therefore, it was expected to cover all topics taught throughout junior or senior secondary school.

This broad coverage limited the depth of cognitive skills that could be assessed. With so much content to test and limited time, it was difficult for the National Examination to measure reasoning or deep understanding. As a result, most National Examination questions tended to assess memorization.

It should be noted that the Ministry had made efforts to include questions that measured reasoning in the National Examination. However, these efforts were not optimal because the examination was burdened with the requirement to test mastery of the entire curriculum.

This limitation does not apply to the National Assessment. Because it is specifically designed to evaluate the education system, it is not burdened with assessing students’ mastery of curriculum content. As a result, the National Assessment can focus on the most fundamental learning outcomes as indicators of system performance.

In this context, the National Assessment measures students’ literacy and numeracy through an instrument known as the Minimum Competency Assessment (Asesmen Kompetensi Minimum/AKM). Literacy refers to the ability to understand and evaluate written texts, while numeracy refers to the ability to apply basic mathematical concepts to solve problems.

As foundational competencies, literacy and numeracy reflect learning outcomes across multiple subjects. Reading habits and skills cannot be developed solely through Indonesian language lessons, but also through social studies, science, civics, religious education, and other subjects.

Similarly, numeracy—the ability to think logically, identify and formulate problems, and solve them using conceptual tools—cannot be developed through mathematics alone. Science, social studies, and other subjects also play important roles.

Thus, the overall quality of teaching in a school can be indirectly assessed through students’ levels of literacy and numeracy. Because of this focus, the National Assessment is not burdened by overly broad content coverage, and AKM questions can be designed to measure reasoning and deep understanding.

What does all this mean for students? What do students need to do?

If the question concerns preparation for the National Assessment, the answer is: nothing. Participants are selected randomly, and the results have no consequences for those who take part.

Therefore, students do not need to undertake any special preparation for the National Assessment. Students in Grades 6, 9, and 12 should simply focus on school examinations that determine graduation, as well as other examinations used for selection into the next level of education.

Parents also do not need to take any action related to the National Assessment. There is absolutely no need to enroll children in AKM tutoring programs that are now being aggressively advertised.

What about teachers and school principals?

For 2021, teachers and principals have nothing to worry about. The Minister has stated that the 2021 National Assessment results are intended as an initial baseline for mapping the quality of the national education system. These results will not be used to evaluate the performance of schools or regions.

In the long term, however, the National Assessment implicitly demands improvements in teaching quality. The focus on reasoning through literacy and numeracy is the Ministry’s way of encouraging teachers to change their teaching practices.

To develop literacy, teachers need to encourage students to read widely—not only textbooks. Teachers also need to teach students how to discuss and evaluate the information they read, rather than merely summarizing or repeating it.

For numeracy, teachers need to ensure that students develop number sense and an understanding of basic arithmetic from an early age. Teachers also need to guide students in solving complex problems—problems that require discussion and reasoning and cannot be solved through memorizing formulas alone.

From the Ministry’s perspective, reforming the evaluation system is an effort to improve the overall quality of education. The Ministry appears to recognize that evaluation should not stop at judgment; it should lead to positive changes in teaching practices.

From the perspective of practitioners in schools, however, this policy change has generated anxiety. This reaction is understandable, given past policy changes that often did not bring relief but instead caused trauma.

In this context, skepticism toward the National Assessment is natural. Some teachers have even mocked the change, saying it is merely replacing the letter “U” with “A.” Building public dialogue around education policy reform is a shared responsibility among all education stakeholders.

This article is a small contribution to that effort. Hopefully, it helps readers understand the rationale behind the transition from the National Examination to the National Assessment, while also reducing anxiety among students, teachers, and school leaders as they navigate this change.

Note: Official explanations and sample questions for the National Assessment (AKM component) can be accessed on the website of the Center for Assessment and Learning, Research and Development Agency and Book Center, at:

https://pusmenjar.kemdikbud.go.id/AKM/